Now complete, DESI is poised to begin its search for answers about dark energy

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, which will map millions of galaxies in 3D from a mountaintop in Arizona, has reached its final milestone toward its startup.

Even as the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, or DESI, lies dormant within a telescope dome on a mountaintop near Tucson, Arizona, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the DESI project has moved forward in reaching a final formal approval milestone en route to its startup.

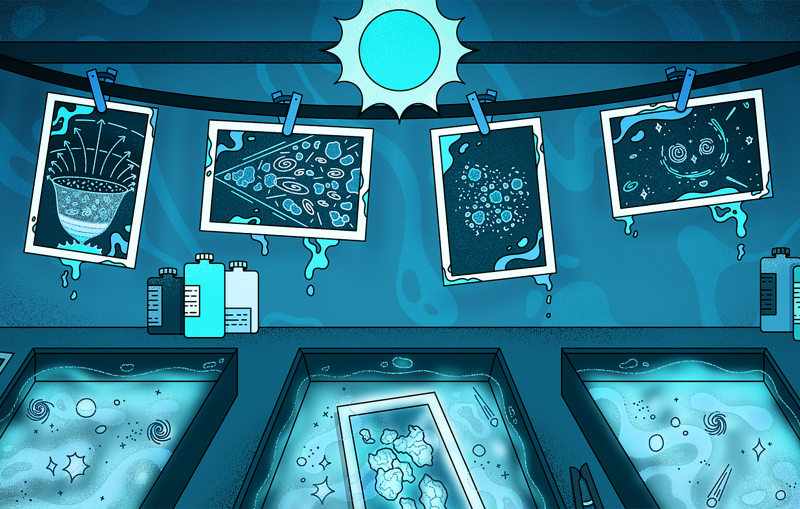

DESI is designed to gather the light of tens of millions of galaxies, and several million ultrabright deep-sky objects called quasars, using fiber-optic cables that are automatically positioned to point at 5,000 galaxies at a time by an orchestrated set of swiveling robots. The gathered light is measured by 10 devices called spectrographs, which split the light into its spectrum.

These measurements help scientists map the universe in 3D and learn more about mysterious dark energy, which describes the universe’s accelerating expansion. They could also provide new insight into the life cycles of galaxies and about the cosmic web that connects matter in the universe.

After DESI passed a federal review in March, members of a federal advisory board formally approved the completion of the project on Friday, May 8. DESI was designed and built through the efforts of a large international collaboration that now numbers about 500 researchers at 75 institutions in 13 nations.

“When we started, DESI was just an idea, and now it’s a real thing that works, this amazing instrument to do our survey,” said Risa Wechsler, the director of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford and the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Wechsler, who has been part of DESI’s science team from the beginning and served as co-spokesperson from 2014 to 2018, said she is most excited to dig into flood of data that will start to flow once the instrument starts up again. “It’s going to be a big playground,” she said. “I’m just excited about all the questions we can answer.”

Chia-Hsun Chuang, a research scientist at KIPAC who co-chairs the DESI cosmological simulation group, which is tasked with designing and testing the sophisticated systems that analyze DESI data, said his team is keeping busy while the instrument itself is locked down. “We will have an amount of information that has never before been achieved,” Chuang said. With the project expected to generate spectra for tens of millions of galaxies over five years, he said, “we really need to make sure our data pipeline can deal with that much data.”

“This is the culmination of 10 years of hard work by an incredibly dedicated and talented team, and a major accomplish for all involved,” said Michael Levi, DESI project director and a scientist at the DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the lead institution for the project.

“We understand and appreciate the extraordinary privilege we have been given to work with this instrument – and even more so during this challenging time, as we continue as scientists to explore what lies beyond our world.”

In mid-March it became clear that a final testing phase of the instrument would be abruptly suspended due to the temporary shutdown of most activities at Kitt Peak National Observatory, where DESI is located, to reduce the risk for the spread of COVID-19.

Project participants moved quickly to capture a large, last batch of sky data during the March 14-15 weekend before the instrument was temporarily shuttered the following week, and that data proved useful in the project’s review for the construction completion milestone, known as Critical Decision 4, or CD-4.

For several months before the temporary reduction in operations at the Kitt Peak site, which is a part of theNational Science Foundation’s NOIRLab, researchers had engaged in DESI observing runs to troubleshoot technical snags and ensure its components are functioning properly.

Now, project participants say they are looking forward to a return to DESI testing in preparation for its startup and 5-year mission.

“Just from the first few nights on the telescope, before we had to shut it down, we already have data that’s really interesting to look at,” said Wechsler. “Even in the first year, we’ll have more spectra than have ever been taken by all other instruments. DESI is going to give us an extremely powerful look at the universe.”

DESI is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science; the U.S. National Science Foundation, Division of Astronomical Sciences under contract to the NSF’s NOIRLab; the Science and Technologies Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; the Heising-Simons Foundation; the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA); the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico; the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of Spain; and DESI member institutions. The DESI scientists are honored to be permitted to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak), a mountain with particular significance to the Tohono O’odham Nation. View the full list of DESI collaborating institutions, and learn more about DESI here: www.desi.lbl.gov.

Editor’s note: This article is based on a press release from the DESI collaboration.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.